Erik ReeL talks about his painting, background and early art experiences, and what leads him to paint as he does.

Erik ReeL talks about his painting, background and early art experiences, and what leads him to paint as he does.S805: How did you arrive at your current imagery? Your previous work was figurative with highly abstract elements and now the figurative elements have been completely cleaned out of the work since 2009.

ER: Cleaned out is a good way of putting it. In the tradition of Christian asceticism there is this idea of kenosis where a monk clears out all attachments to the material world, and attempts to clear out everything in the mind. Not as a search for nothingness the way it might be in, say, a Zen practice, but, rather, the idea was that if the human mind was cleared out of all earthly attachment, then something greater would rush in and fill the void and the disciple would be enlightened with that which is beyond the material world.

Paul Berger, the English critic, revived the term to mean a bleeding out of meaning in modern art. For the mystics it was intended to create an emptiness so that something with a greater, or deeper, or higher meaning could reveal itself. The idea is there in the thinking of the Church Fathers, the Patristic era of people like Origin of Alexandria.

S805: So how does this relate to painting or your painting?

ER: I wanted to get to a different place in my painting, one that was not so tied to the material world, that did not affirm materialistic values by referring back to the material world. So I initiated my own process of kenotic elimination in myself and my painting. This meant bleeding all references to the material world out of my own work.

S805: When most painters do that, they end up with a very reductive process of abstraction. Isn’t Malevic’s work the ultimate result of that kind of process? Or Ad Reinhardt’s? Isn’t that the path to Minimalism?

ER: That was the Modernist approach because Modernism did not really attack the underlying materialism or the Materialist philosophy that underpinned modern technological society. Post-Modernism goes further and extends the underlying materialistic philosophical bias of post-industrial societies. This is one of modern society’s problems: we accepted science and technology as the main drivers of our civilization, but as we accepted the enlightenment of rationalism and science, we also accepted something else, a philosophical position that is not necessarily inherent in science: we coupled science with a materialistic philosophy. It is not necessary to do this.

S805: So you side with a more religious point of view?

ER: No, I am not talking about religion vs science or rationalism here. Materialism is a philosophy that not only reiterates the priority of the material world, it posits a single material reality as the only possibility. No subtler realms exist. That science also adopted this philosophical position implicitly, is a non-scientific act. It is a philosophical position. It is extraneous to science. You can be a non-materialist and not be religious, nor even believe in the divine, let alone a god. In Plato’s Symposium, for instance, Socrates presents an alternative with a hierarchy extending far beyond the single level of matter and physical energy that materialism presumes. There are many alternatives. For example, the Perennial Philosophy of Ficino and Pico della Mendoza that drove the Italian Renaissance and revived by Aldous Huxley.

S805: And art? How does this have to do with your art?

ER: Modernism, keeping itself tied to materialism, always approached the reduction, or kenosis, or bleeding out, as a purely physical, materialistic process. This means limiting it to reducing the material means or a reductive formalism or both. So for the Modernists the inherent materialism limits them to a literal, material, purely visual surface level of reduction where abstraction leads to a reductivist elimination of formal means. So we get Malevic’s white square on a white square, or, later, Reinhardt’s black on black paintings, as you suggest. In that sense, you are quite right for a Modernist or Post-Modernist, since both still work within a materialistic continuum.

But I’m not a materialist; so I ended up with something more like the what Origin of Alexandria proposed: a new richness with emotional, psychologically charged inner meanings, rather than the reduced formalisms of some sort of Minimalism. The first kenotics were searching for God. Something from Beyond. Which implies that I am also searching for something from beyond. Though, on the other hand, I have no reason to believe I am searching for anything anyone would call God.

S805: So you would say this is evidence for you being a Post-Modernist?

ER: Actually it would mean I’m not Post-Modernist either. That is another, very long, discussion. But basically, if you look at all the versions of Post-Modernism out there, you have to come to the unavoidable conclusion that for all its responses to Modernism, the underlying Materialistic philosophical bias is retained, in many cases, strengthened.

S805: But a lot of Post-Modernism is anti-science!

ER: But philosophical Materialism and science are independent of each other. You don’t automatically rid yourself of materialism by being anti-science. That is blatantly not true: it is easy to think of people who have no interest, or even knowledge of science being materialistic. Materialism has been around forever. Science is a very young tweak in human thought.

S805: Science is a tweak in human thought?

ER: In the great scheme of things, it is a very late entry, and even now, not adopted by a lot of people. But it is an exceptionally important tweak. We need to tweak it further, though: to decouple it from philosophical materialism. Many scientists that I know or have met have personally done this already.

S805: OK. So anti-science doesn’t get you anti-Materialsim … automatically, and science doesn’t have to be hooked to materialism. But I want to understand this Post-Modernist thing a bit more.

ER: I don’t want to get bogged down in a discussion of Post-Modernism. For one thing, Post-Modernism has been used to refer to many different things, often conflicting positions. We can’t just throw around the term “Post Modernism” like that and be clear.

For one thing, the term was first applied narrowly to a specific school of Architecture that was essentially Classicist in intent, but which wanted to retrieve a few things, such as greater emphasis on context, and move forward into a less geometrically formalist direction than what Modernism originally meant in architecture. Which, by the way, was originally also primarily applied to architecture and design, especially industrial design: which was Le Courbusier, Bauhaus, De Stijl, and Constructivism. It was only later widened to take in an entire era, all the arts and culture. It now means something much wider.

S805: The whole Modern world.

ER: Well, yes, there has always been that, but I am using it to refer to what happened at the beginning of the last century: something that fights for some sort of more generalized formal global universality in culture and art, something that originally meant free of all cultural bias. But that was not everywhere evident, or not practically possible. Further, there was a problem: it’s tendency toward idealism or a totalitarian approach. Remember, the Futurists, clearly Modernists, also supported Fascism.

So the Post-Modernist reiteration of multi-culturalism, context, supporting sub-cultures while de-privileging monolithic ruling cultures, and its consequent war against all forms of marginalization, was a necessary and healthy corrective to the annihilating de-culturalization of classic Modernists’ assumptions. But this also means, that in practice, Post-Modernism worked as a corrective, or alternate path within the same philosophical and historical continuum of materialism. The post-industrial, post-Modernist world is as materialistic as the last century ever was. With our gadgets and computers and wealth and media and wars over resources, we’ve become ever more obsessed with the material world.

Worse, the non-materialistic alternatives have become increasingly ugly, unpalatable, many descending into mindless militant fundamentalism, and aggressive dogma. So Post-Modernism has landed us in yet another materialist soup, even more aggressively so. Thus Post-Modernists still tend to work within the context of philosophical Materialism. My work doesn’t.

S805: but as a painter, you are constrained to the material. It is an inherently physical, material medium.

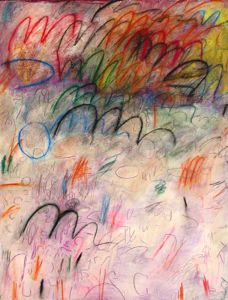

ER: But I like it because it can be the least so. My paintings are flat, painted with the thinnest layers with exceptionally liquid paint. I avoid all intentions, references, and tactics toward the material or three-dimensional, or references to objects. I reject the whole gamut of Modernist and Post-Modernist gimmicks for introducing references to thing-ness and the object-ness back into painting. I consider this whole approach as corrupt. I reject any push toward three-dimensionality or object-ness.

S805: Because it is corrupted by the material world. But I get a sense of space when I look at your paintings.

ER: but it is a psychologically-charged space. It is purely perceptual, non-physical. It is created by the cognitive processing inside your brain, not a reference to the physical, external world. The means are still radically two-dimensional. They are cognitive, thus about as non-material as a physical medium like painting can go.

S805: So you are positing some sort of dichotomy between internal/anti-material against the physical, external world which is linked to materialism. A sort of noumena verses phenomena kind of thing as a way of contexting art?

ER: I’m not sure I’d portray it in those terms. Partly, because those terms imply an acceptance of aspects of Kant and his successors that I do not agree with. But that is a discussion that would derail us into technicalities that are beside the point.

S805: Ok. So how do you see it?

ER: Obviously, painting has to work with the material. Plato didn’t eliminate the physical, it was his first level of reality, he de-emphasized it. Socrates, in the Symposium, claims we humans cannot escape it. It is a matter of emphasis. Even an ascetic still eats; he just doesn’t eat very much.

S805: So it is a matter of emphasis.

ER: Emphasis partly, more about priority and focus. The end reveals the difference: I didn’t end up with Malivic’s white squares or black on black, or any other kind of reductivist or Minimalist result. I ended up with complexity, with visual richness.

S805: There are definitely more minimalist passages and some works are rather, shall I say, sparse.

ER: There may be a certain sparseness. I like sparseness. A certain minimalism, but not Minimalism with a capital “M”. No, what I meant is that the process resulted in much richer paintings, a much more complex painting for me than before my kenosis. I experienced—and the paintings revealed—something richer. This is more akin to the original intentions of kenosis: emptying the material world out of my paintings did not result in nothingness, or a minimalist reduction; instead it opened the paintings up to another realm, possibly from Beyond, from Another Place, which is exactly how I experience it. These paintings feel like they come from Somewhere Else. From Another Place. They well up from inside of me, but out of sight of my intellectual mind.

S805: Do you see this Other Place as a psychological, internal place, or something transcendent, spiritual?

ER: Beyond my ego and intellect, certainly. Other than that I cannot tell. The Hindus say Brahman is Atman.

S805: Meaning?

ER: The deepest internal reality is the all-encompassing universal external reality. They are the same. Beyond a certain point, that point being the reality of our intellect and perceptual distinctions, at the extremes, the deepest internal reality and most encompassing reality are the same reality. It is not humanly possible to distinguish, ultimately, the deeply psychic from the transcendent.

S805: That certainly is not in line with most of Western thought. In our Western philosophical tradition the extreme internal and extreme external are at opposite ends of the spectrum. You’re either going deep down inside or up big outside. Not that deep inside is the same as big outside.

ER: Yes, neither, I suspect, is anyone else anywhere else. I suspect that “Atman is Brahman” was seen as a puzzle and contradiction at all times, even on the Indian subcontinent. However, it definitely eliminates certain technical difficulties.

S805: I wouldn’t know about that. Does anyone care about that, these days, anyway?

ER: Maybe not. But where you stand regarding Materialism, whether you know it or not, leads you to conclusions and very different actions. If you really are a philosophical materialist or not is going to determine a lot of things in this life.

S805: Like what?

ER: Well, as an example, a society that is deeply, philosophically, materialist, like ancient Rome, or the present United States, will start emphasizing the material in art. To focus on what is new solely in terms of its medium is a totally materialist conceit, for example. Only materialists care about that.

S805: So it skews the whole cultural viewpoint on art?

ER: For one thing, it attempts to turn everything into either objects or entertainment.

S805: Earlier, when I asked what you meant, I was thinking on a more personal level.

ER: OK, everyone wants some level of material comfort, some level of material wealth—like Socrates said, we don’t want to deny our bodies—that is one of the mistakes of religious purists. As Socrates said, moderation in all things. But a truly philosophically materialistic culture will tend to a whole array of things, both exemplified by ancient Rome and the present United States: they will emphasize the material at every level and the conquest of the material world and all the hubris that goes along with it over deeper psychological values.

ER: OK, everyone wants some level of material comfort, some level of material wealth—like Socrates said, we don’t want to deny our bodies—that is one of the mistakes of religious purists. As Socrates said, moderation in all things. But a truly philosophically materialistic culture will tend to a whole array of things, both exemplified by ancient Rome and the present United States: they will emphasize the material at every level and the conquest of the material world and all the hubris that goes along with it over deeper psychological values.It means a greater emphasis on technology, rather than internal understanding; it means a society of engineers, it means war, dominating the material world, literally, with a huge military, engineering capable of building the best weapons and the mentality to use them. It means a culture skewed toward war, violence, physical control, domination, and fulfillment of every physical need, but against subtlety, nuance, insight, understanding, love, and emotional fulfillment. On the personal level, it means you get a world where you can get everything possible physically, but are emotionally bankrupt. Physical riches in a psychic wasteland.

But worse, the military and economic powers that think this way end up creating a world with enormous physical inequities, with mind-numbing poverty alongside seemingly limitless physical gratification, which is a feature common to both the Roman Empire and our current world order.

This is the flipside of both Modernism and Post-Modernism, because it is linked to something common to both: an underlying bias toward philosophical materialism. Philosophical materialism ultimately gives you the world we are living in today.

S805: So you obviously don’t want to feed this.

ER: Exactly. My challenge was to find a way to create art that would inherently feed a different philosophical orientation and I feel I’ve succeeded. Even if a given viewer doesn’t consciously realize it as so.

S805: I’m not sure I follow how that is so myself.

ER: The great thing is you don’t have to. The work works whether you follow or understand it or not. If you give it some time and look at it. You don’t have to figure it out, so to speak, just experience it and leave it at that.

S805: But people are going to try to figure it out. They are going to try to de-code it: your titles encourage this with their multiple meanings and all. So there is this fun game to play while looking at the work. “Oh, look, I recognize that and that goes with the title in a way I can see,” and so on.

ER: Fun games for the intellect. But this work is not just for the intellect. It is for a deeper layer of your psyche, or your mind. Not to figure out, but to experience. One of the ways to get in there is to distract the intellect so that it doesn’t get in the way. The titles help with that.

S805: The titles are a ruse for the intellect?

ER: They work. That is all that is necessary.

S805: Do you see painting as some sort of way of working on people’s psyche or changing them?

S805: Do you see painting as some sort of way of working on people’s psyche or changing them?ER: Doesn’t everyone see painting as working on the psyche? I don’t know about changing anyone. I know painting and art has changed me, and I’ve seen it in others; but in general, I don’t know how much art or painting changes anyone or anything. In the end, that could very well be a romantic delusion. A very useful delusion I suspect.

S805: Earlier you made a connection between purism and totalitarianism.

ER: Purism leads to some form of totalitarianism. Our modern world has a terrible tendency toward totalitarianism and totalitarian thinking. Even our businessmen want total monopolies. Everyone wants to control everything, not just some things, but everything. Fundamentalism, of every stripe, is just another manifestation of the totalitarian flavor of our times. It used to be that Fundamentalists would go off and set up a separate community and try to live there apart from everyone else. Live and let live. Now they want to take over the world and kill everyone who does not agree with their fanatic purity. It is really quite insane. Purism is madness. Reality is not like that. It is always a complex balance of forces seeking equilibrium. Any attempt to make things otherwise ends up in disaster. Fortunately, history has shown that reality takes its revenge on all purists, eventually.

S805: I see a lot of balance and equilibrium in your painting.

ER: They are resolved. Like music. The human mind responds to resolution. That is where their completeness comes from; resolution determines when a painting is complete. That is when I stop working on it.

S805: You just answered one of my other questions: How do you know when a painting is done? Does that mean that they are resolved, or feel complete at only that moment? They never seem balanced or resolved or whatever before?

ER: There is a moment when the whole image comes together and is resolved. Of course, there is always the possibility that, like a symphony in music, there are lesser resolutions along the way.

S805: Your present painting is a lot like drawing. When did you start drawing?

ER: When I was six.

S805: What were your influences?

ER: My mother was a watercolorist. Our next-door neighbor had run a lithography shop and had been a rather good painter when he was young. Small Barbizon-style oils. He gave me all his litho pencils. One partly empty box, which I still have today. I loved drawing with litho pencils. When I was 14, he had a stroke, I helped take care of him, listened to the stories of his life and played his classical records for him. Seeing him approach death, having him share his life and stories with me was a very formative experience for me. At some time it must have been much more common for younger people to share this kind of interaction with their elders: to watch death. After all, in a village, or tribe, and certainly through most of human history, teenagers and the young must have experienced their elders and their deaths as a regular occurrence.

S805: You said you were drawing at six. When did you start painting?

ER: My first serious painting was an oil. I was 12. My grandmother had given me pan watercolors much earlier. I didn’t like them. They seem too washed out to me. Later, when my grandmother took me to a museum and we were walking through the Kress Collection room, which is all this pre-Renaissance painting, I saw this patch of red—red egg tempera where the red had been laid down in multiple transparent layers until it attained this deep, rich red that the light just went down and into and drowned—and I said to her, “See! This is the kind of color I want!”

S805: what did you paint? Do you remember?

ER: Oh, yes. That first painting was a crucifixion, very baroque-like—I’d been inspired by a book on Rembrandt of my Grandmother’s—with deep shadows and a shaft of light coming down from the upper right illuminating Christ. My Jesus looked very Semitic, very dark-skinned with kinky black hair. Not the blond knock-offs of Durer’s infamous self-portrait Christ of today.

S805: Where do you see yourself in terms of Southern California art?

ER: I don’t.

S805: What do you mean?

ER: I would never consider myself a California artist any more than Picasso would have considered himself a French artist. I’m from Seattle. I consider myself, if anything, a Seattle artist.

S805: Is there that much of a difference?

ER: Yes, I am working with totally different starting and reference points. For me, everything started with Tobey. And I mean the White Writing Tobey, work that I loved when I was a kid. I also, back then, liked certain works of Guy Anderson, and Kenneth Callahan, who I met during an exhibition of his at the Henry Gallery.

S805: What did he say?

ER: He was very encouraging of course, a bit surprised that someone my age was so passionately interested in painting. He asked me what I liked about his work. I said the big abstract brushstrokes running through his paintings.

S805: What did he say to that?

ER: He said I had a very advanced view of art and he wished others thought that way as well.

S805: I can see the influence from Tobey.

ER: You know, that whole Northwest Mystics school did a lot of black, white and umber greys. Color, for them, was often burnt or raw sienna. It’s a dreary, Puget Sound rainy palette. Even when I was in art school there in Seattle, a lot of people were still using that kind of palette. When I was a kid, I had this idea that when I grew up, I would do some paintings like Tobey’s White Writing, only in full color. Which I did. It is a small series of paintings, each titled Technicolor Tobey.

S805: What other artists have influenced you?

ER: I learned a lot from Titian- not his grand machines, but his smaller paintings where he seems to have painted the whole thing himself, in which case, he lays in his paint in beautifully brushed, thin layers. I learned a lot about painting thin from him. Color was originally my main challenge and now, I feel, strength, and to that I owe the three great colorists, Klee, Matisse, and Rothko. As a teenager my natural drawing style was very linear, very Matisse-like. So it was natural when I first started painting to see Matisse as a starting point. But Klee, with his interest in the more graphic nature of markings, and his darker, more Northern palette, was a more natural point of reference psychologically.

S805: That certainly carries on into the current work.

ER: Yes. It’s more of a cycle. A return. I did not get here linearly, but over a cycling between figurative and more abstract approaches until I decided to strip away everything foreign and return to my most natural inclinations.

S805: Why did it take you so long? You’re now 60. A lot of artists do their stripping away when they are 20.

ER: This is my mature style. And I reached this point when I was 57. A lot of painters don’t reach that point until in later years. For Titian he was well into his 70s. So I don’t see I’m being so late. It’s just that I haven’t tried to exhibit much.

S805: But you did exhibit, and were known to some important people, such as Castelli and Gene Barto.

ER: Yea, but I never pushed it. I couldn’t get fully behind it because I always knew I was after something else. I had something else in me.

S805: Wow, twelve to 57, that’s what? Forty-five years. That’s a long time to look for something.

ER: Yes, but I always knew I wasn’t where I wanted to be. But then, at the beginning of 2009 I knew I had it, I had found the gateway to what I was searching for.

S805: That‘s still a long time to look for something.

ER: Yes, but not unlike other painters. Cezanne takes a long career and time to get to what we consider Cezanne. We are fairly certain Titian apprenticed, probably at 13, but he doesn’t set up a studio until he’s probably 54, and still achieves a stylistic breakthrough almost 20 years later.

Some meet early success: Goya, and Rembrandt, for example, were wildly famous young; but later realize that their early, very tight technique isn’t at all what they really wanted and achieve a wholly different approach only toward the end of their lives. And people, Americans especially, tend to forget that with a few exceptions like Pollack and DeKooning, most of the Abstract Expressionists didn’t even have shows until into their fifties. The next generation with Frankenthaler and then seemingly everybody, getting their big shows early is really, in terms of the overall sweep of art history, more the exception rather than the rule.

S805: Couldn’t someone say this is all an elaborate justification on your part for not having found your style until your 50s? You still exhibited and were trying to exhibit all this time.

ER: Not really. I haven’t ever tried, really, to exhibit, until now. This year is the first year I am trying to exhibit. Sure I have exhibited. But that is more from being around and talking to people and the exhibitions that have come about have more or less evolved in the natural course of things, almost accidentally. There has never been a push to exhibit. Until now. Now that I am 60, I have decided that I want to exhibit, to share my work.

S805: I find that a rather amazing confession.

ER: Perhaps. But I am only looking ahead and working in the moment. My past art does not interest me that much.

S805: But some of it, such as the later rather abstract figurative paintings are highly regarded and there must be a market for them.

ER: That may be so, but I am doing by far the best work of my life right now, and at a pace, about 140 works a year, capable of sustaining an exhibition schedule. It is time for people to see it, for it to be part of the discussion.

S805: The work has a distinctive and strong hand.

ER: All my life, people have pointed that out, people who have seen even a few of my works are able to recognize a work as mine. People generally have always been able to recognize my work as mine without a signature. My hand is my signature.

S805: It seems lately that a lower-case “e” is your signature. You’ve almost co-opted the letter e as a signature.

ER: That is somewhat true in the new work. It is a work full of single marks, so I needed a single mark signature so that I didn’t disrupt the image if I signed it in front. So the lower-case e, which appeared already anyway in previous works, became a natural signature.

S805: A way of making your mark. Literally.

ER: Yes. Making my mark. That is the new signature.

S805: Speaking of making marks. What about the idea of coding or encoding in the work? People talk about that.

ER: There is some coding in the work, and any mark-making is going to involve encoding. That is how the mind works. Even inchoate marks encode

S805: How, if they are inchoate?

ER: Color, hand, treatment, location, clustering and grouping, through repetition. Feelings, a sense of internal space or world, a personally inhabitable world, all become possible. That amounts to a lot of encoded meaning. You just can’t get literal de-codings like translating French into English out of the marks, because they aren’t a formally constructed language. But they do constitute a distinct visual language, if you will, that encodes multiple layers of meaning.

S805: OK. There are explicit images or signs in the work, but you’re talking about all the marks, right?

ER: Right. Of course, there are more literal images that can immediately be de-coded or recognized.

S805: What about those? Like the vaginas or crosses? I am never sure what you intend with the crosses. They don’t seem religious and I don’t get the feeling that that is a direction you would go.

ER: Yes, there are the yonis. There are several versions of yonis in the work, including traditional Tantric signs. And yes, the crosses, the roods, are not intended as Christian symbols. A black cross, for me, is a reference to the awareness of death. In particular, your own death. So they are about the awareness of our own mortality, in the moment. The rood goes beyond that, as a symbol of homecoming in Norse culture, as a reference to the fact that Skandinavian culture was both a literate and mature culture before Christianity imposed its very foreign ideology on it; before it was independent of Christianity. The rood is a reminder that Christianity was imposed on Scandinavia by the sword, by force, against our will, so for me it is a reference to the evil and darkness of religious totalitarianism.

S805: So an anti-Christian sign almost. What about other influences? What about your teachers?

ER: One of the people who influenced me, more as a mentor than as a teacher was Jacob Lawrence.

S805: How do mean mentor rather teacher?

ER: Only that I attended his critiques, but never took a formal class from him. I was fortunate to have worthwhile interchanges with him. Lawrence was a gifted teacher in every way, a true mentor and guide for young artists.

S805: Anyone else at school? I see your bio lists Crone, Spafford, Tsutakawa, Hsia Cheng, Dahn.

ER: Hsia Cheng offered a total immersion into Chinese brush, philosophy, and aesthetics. He was a type of Confucian scholar-esthete that existed for many centuries in China and probably no longer exists and will probably never exist again. He would quote a passage from Chinese literature or philosophy at length, from memory, in Chinese, then translate and comment, then invite response. I imagine most higher learning worked like that at one time. Very different from today.

Rainer Crone was probably the best art historian there before he left for Yale.

I learned the most in the studio from Michael Spafford. What I got from him was more of an attitude than anything, a natural give and take and process of working on a painting that fit my natural inclinations and approach to painting. In drawing, working in a mode more similar to his opened up a possibility of unifying my drawing and painting, wedding them more tightly. Up till then my drawing and painting were in two different worlds technically, and I was having trouble connecting them, which seems funny today, because now my drawing and painting are indistinguishable from each other.

Dahn had studied with Albers at Yale and essentially taught an amplified version of Albers’ course that was the foundation for his classic, Interaction of Color. That gave me a context for understanding color from a more technical point of view which I was able to use and extend when I later taught color theory.

I studied sumi-e from Tsutakawa. He primarily taught sculpture and is widely known around the Pacific Northwest for his abstract fountains, very totemic cast fountains. A watercolor course was required, but we had the choice of either sumi-e or traditional Anglo-American-watercolor-society-type watercolor.

S805: I suspect it was no choice if you had already been into Tobey. So you both studied sumi-e.

ER: Exactly.

S805: This would have been in the early to mid-seventies?

ER: Yes. The University of Washington painting department was at the tail-end of its peak at that time.

S805: Thank you, I look forward to your solo show at 643 Project Space. That is one of the best exhibition spaces in the region outside of the major cities; I am sure your work will look very good there.

For more information on Erik ReeL please visit his website